The weekend passed without incident. I was bored nearly to tears, except for the abject fear of impending eye surgery. I spent most of Saturday on the first weekend of June 2016, asleep because of my late visit to the hospital. Sunday, I sat around the house, afraid to overexert, as if my sacrificed time could somehow save my travel plans.

Barbara drove me to the doctor’s office on Monday morning. I was told that I had an 8:00 a.m. appointment. Apparently I shared that appointment time with a dozen other people, all being seen by the same doctor.

The office was tucked away off of two main roads, down the street from a large ophthalmology practice on Capital Circle, the loop that runs most of the way around Tallahassee. I would not be going to the big prominent ophthalmology practice.

Tallahassee has a few older medical practices that still operate in aging buildings, with dimly lit waiting rooms. By contrast, most of the larger practices have brightly lit, well appointed offices with care put into interior design and a decidedly upscale, nearly retail appeal to the space. A fancy office should not be the deciding factor in choosing medical care. However, I’ve found that it speaks to how the principal physicians view the patients.

I had discovered the secret to quick attention with most medical providers in Tallahassee is to mention that I’m training for a race. At least it works with the orthopedic practices. So with most doctors I see, appointment times are kept and are usually very accurate.

The cattle call waiting room was something I hadn’t experienced in a long time. Rows of older worn chairs sat mouldering, filled with seated patients in a dimly lit room, roughly oriented towards a small reception window and a large flat screen television set, droning with commercial laden daytime television. I’ve found that ophthalmology practices generally attract older patients with diseases of the eye resulting from age. I was markedly younger than most of the other patients, and by what I could see with my one good eye, significantly more active than anyone in the room.

Eventually I was led into a narrow hallway with more seated patients in between imaging stations. Essentially, patients were stacked up like like flights at a busy airport in every possible location, except the exam rooms themselves.

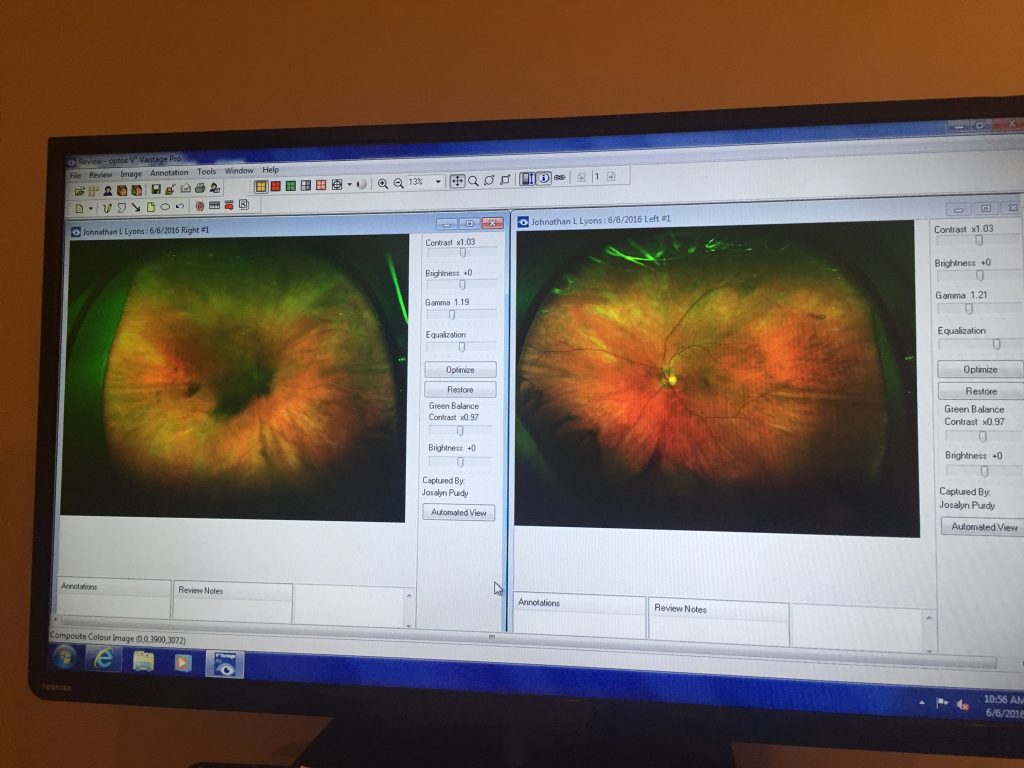

My wife and I were guided from one high tech imaging station to the next with stops in between where I waited in a chair, looking at featureless white walls. Finally, I was led to a room with a large monitor displaying my retina. The bald and bearded doctor could not tell me the extent of the damage, I was told. The large black spot in the middle of the image was a blood clot in my eye, and it was in the way of getting a clear view of my retina. I was scheduled for a vitrectomy.

During a vitrectomy, the jelly like interior of the eye is sucked out and the surgeon re-inflates the eye with saline, or in the event of retinal repairs, an air bubble. It’s a procedure created in my lifetime, meaning that had I lived a few decades earlier, I would have been left blind without hope of seeing again. The patient receives a nerve block during the procedure and is awakened during the surgery.

I remember seeing the pale blue surgical blanket over my face. I was extremely nearsighted at the time and without my glasses, the blanket was a fine mesh with pinholes of light passing through. As I oriented myself to being covered head to toe for a sterile surgical field, I heard the surgeon say, “I’m not looking forward to telling Mr Lyons that he’s not going to the Virgin Islands.”

I responded, “I heard that.” I don’t remember much of the following discussion, until the procedure was finished and I was moved to a recovery area, except that I was told that my retina was torn.

As a result of the nerve block, I experienced total nerve blindness for the rest of the day, which was a very different experience than the blindness I would experience until my vision eventually returned. Unlike the inability to focus, the neurological loss of vision was a strange sensation. There was no darkness. No glimmer of light or memory of light in my right eye. It was nothingness, nearly as if I had forgotten how to see anything from my right eye, or it was only a dream I had. It’s an experience that I feel inadequate to convey, yet remiss if I ignored it.

My eye was covered by a bandage and a clear plastic eye shield. The shield was a hard shell with holes like a colander, to allow the eye and the wound to breathe. As the afternoon wore on, nearer to sunset, I became aware of a warm glow penetrating the bandage.

A little understanding of optics helps to explain what I was about to experience. I promise to keep this easy. Take an empty, clear glass or jar and look through it. Now, fill the glass (or jar) with water. See how the water makes the light bend and distort how objects look on the other side? That’s what happens naturally inside your eye. In my case, the surgeon had just sucked out that great light bending fluid and I was about to look through an eye, filled with air. The view was underwhelming.

Everyone chooses how they react to adversity. I do what I can with novel situations. My post-op checkup was set for the morning after surgery. I arrived wearing jeans and a t-shirt, a skull and crossbones bandana tied around my head, a toy cutlass about 10 inches long and a stuffed toy toucan.

“Arg! I be here for my appointment, I announced to the receptionist, making the most of my patched eye. No reaction whatsoever. I had plans to find movie and other one eyed characters for my subsequent visits. I had the jacket picked out for Agent Fury of the Avengers. All of it dashed because of a doctor’s office with little sense of humor.

I was led to a dimly lit exam room and my good eye was covered. “What can you read on the chart?” I actually asked, “Is there a chart?” Remember my example of the glass of water? My eye was full of air and the refractive quality of air is very different than vitreous fluid. Add my already poor, uncorrected vision and I couldn’t find the chart. For that matter, I couldn’t find my hand in front of my own face. There were many times that I wondered if the vision would ever return to that eye.

You may recall grade school science classes that the human eye sees everything upside down. That’s not exactly true, but that’s how most people understand it. What really happens is that the retina, the part of your optic nerve that senses light, gets a reversed image of what you see projected upon it, almost like a movie screen and projector. Your brain is wired to see things right side up, but the light inside your eye is projected upside down.

The doctor explained to me that my eye was already producing new vitreous fluid and the fluid would replace the air over the next few weeks. Because the image in the eye is upside down, and the fluid was in the bottom of my eye, it would appear as if my vision was returning from the top down. In the mean time, I was living in a flattened world with only one functioning eye.

Stereoscopic vision (they way you see the world with two eyes) is greatly underrated. Avner went to visit his friend, Michael about a mile away, just the next neighborhood over. I told my wife that I was going to bring him home. I took my trekking poles with me. I live in a hilly part of town and the change in elevation around me makes for great cycling, but with one eye, the changes in elevation make for challenges.

In the late afternoon light, I couldn’t tell whether the darkness ahead of me was a hole I could step into or a shadow cast by the late afternoon sun. My trekking poles kept me upright and my constant poking kept me from falling flat on my face. By the time I made it to Michael’s home, I was happy to have survived the journey that a couple weeks before was only a quarter of my running route.

The walk home was equally enchanted. Everything looked new and different to me. The buzz of the summer insects provided a surreal soundtrack to a simple walk home and the roads I knew so well as to ignore them, were full of peril and just different enough to feel not quite unfamiliar.

After a couple weeks, my vision started to return. As promised, it filled in from the top down. As the fluid approached one third or half way, I became aware that my eye had become a spirit level. My vision was anchored by gravity, any picture hanging on a wall, or any object that was not perfectly level, became an object of unusual scrutiny for me.

In the last few days, as enough vision had returned to start driving again, I became impatient for the bubble to go away. Everywhere I turned I saw that damned bubble and I just wanted to see again. It would take months before I could really be satisfied with my vision.

A couple days after the surgery, I ventured into my office. I struggled to see the screen. It turned out that my right eye was dominant and my prescription for my left eye was out of focus enough to present problems reading my screen.

Walter Hathaway is a tall, white haired optometrist with an easy drawl and a Jeep he parks by his office door. One reason we had been seeing him was that his office is a short walk from our house. So, I wandered to Walter’s office with my trusty trekking poles and explained my situation. He remained professional and calm but very concerned that I hadn’t called him first. I explained the situation with the emergency room but he insisted that I should have called him. Then he became insistent that I should get a second opinion.

After dancing around the subject, it became clear that Walter was uncomfortable with my surgeon’s practice. It was agreed that I would not accept follow up laser procedures being suggested by the surgeon, as it seems they were in the habit of offering services that had questionable benefits and outcomes.

Instead, I was referred to another practice, run more efficiently. They would confirm that my eye seemed to be in good shape, but also advised against any further procedures.

1 Comment